Don’t ask director Andrei Konchalovsky whether his new film in Venice, “Dear Comrades!”, holds a mirror to today’s Russia, recent unrest in Belarus, or even threats to democracy in the United States.

Interpretations are up to the viewer, insisted the veteran Russian director, as the film, shot in black and white, was set to premiere at the prestigious film festival on Monday.

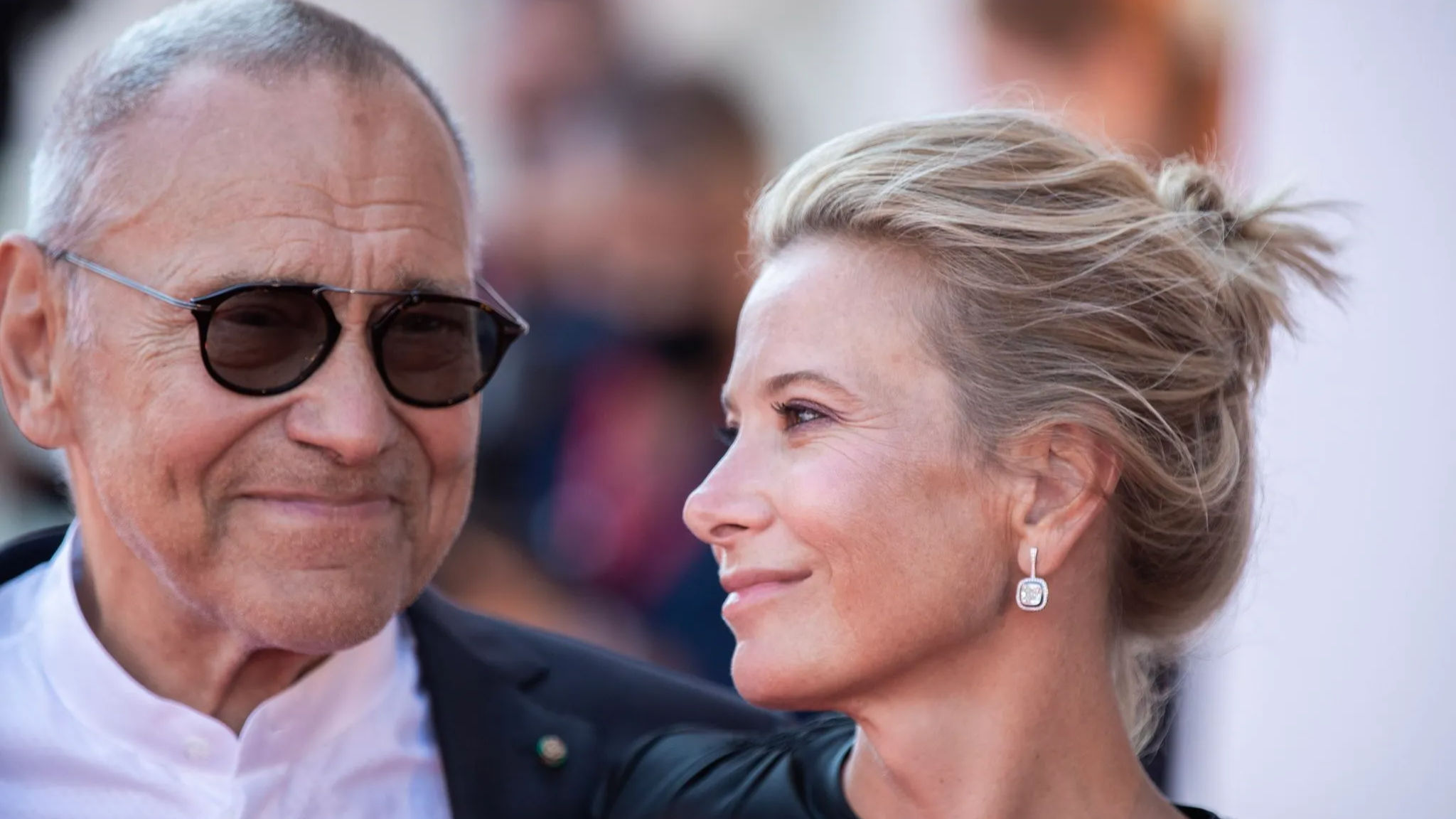

“You can make all the parallels you want,” Konchalovsky, 83, told a press conference. “It’s not up to me.”

The well-oiled machine of state suppression is the frighteningly topical backdrop to Konchalovsky’s film, based on a true story of a 1962 labour strike in the then-USSR, with all its elements having modern-day comparisons.

Protesters are labelled hooligans, propaganda slogans are repeated as fact and if witnesses to state killings are silenced and bodies buried out of sight, then the massacre never happened.

Konchalovsky won two Silver Lion awards for best direction at the festival, in 2014 for “The Postman’s White Nights” and in 2016 for “Paradise.”

With “Dear Comrades!” he said he wanted to make a film about his parents’ generation, who shared unconditional trust in the values of communism but found their idealism betrayed by subsequent events.

The film is about the 1962 labour strike in Novocherkassk, in which 26 factory workers protesting against rising prices and slashed pay were shot and killed by Soviet troops and KGB operatives. Decades of silence ensued, as the massacre was covered up until 1992, with the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Lyudmila, portrayed by Julia Vysotskaya, is a party functionary who early on is eager to denounce the protesters as drunks and criminals who should be swiftly punished for their rebellion.

“We live in a democracy!” shouts her daughter Svetka (Yulia Burova) before the massacre, herself a factory worker sympathetic to the protesters’ cause.

But that faith soon appears naive, as in the wake of the killings a curfew is imposed, witnesses sign non-disclosure agreements and the bloodstains of the victims are covered up with new asphalt.

As Lyudmila desperately searches for her missing daughter among the victims of the shooting, she is tormented by the collapse of her long-held convictions.

“I directed this film like a Greek tragedy and I studied the feelings of those people who lived through these events, notably the tragedy of a woman who always believe in her Marxist ideals,” Konchalovsky said.

“I’m writing a symphony, like a musician. All the rest is up to you, how to interpret it.”

Asked why he chose to shoot in black and white, Konchalovsky said it felt natural for a movie that was “a document” of history.

“Halfway through the 20th century everything was black and white,” said the director.

“Therefore, for me, it seems strange to do this in colour.”