The auteur is dead.

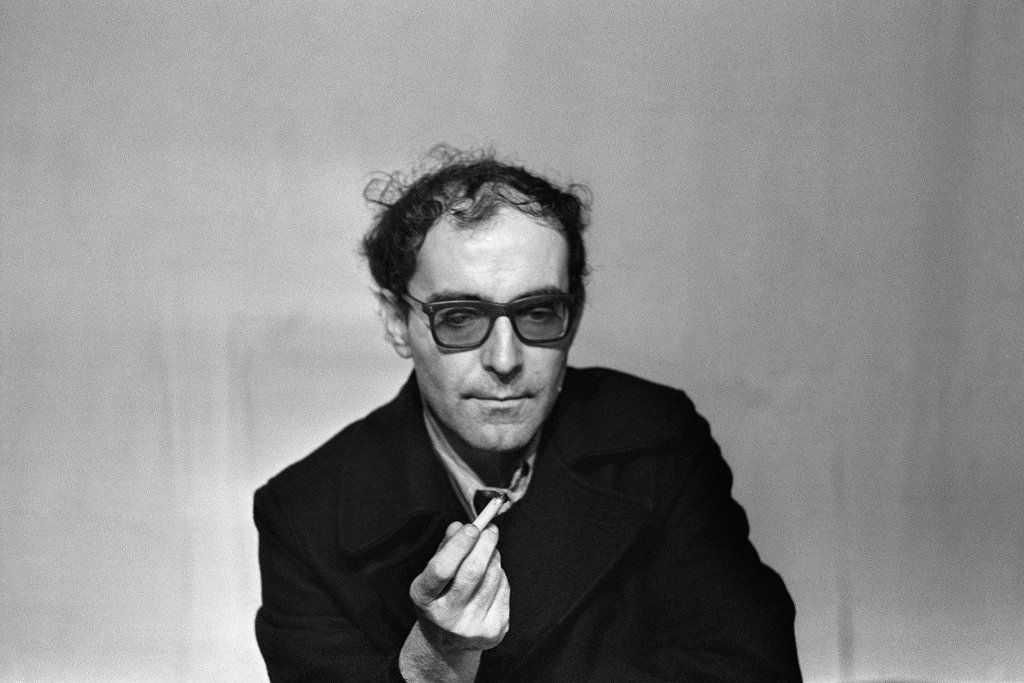

Even in death, he remained the enfant terrible he always was.

“He was not sick, he was simply exhausted. So he had made the decision to end it. It was his decision and it was important for him that it be known,” said an unnamed family source to the French newspaper Liberation, which reported that Jean-Luc Godard died by assisted suicide – a fact later corroborated by his lawyer, Patrick Jeanneret.

Also read: Jean-Luc Godard died by assisted suicide, confirms his lawyer

The newspaper also cited Godard’s 2014 interview on Swiss TV during the Cannes Film Festival, in which he was asked about his thoughts on death. He claimed that he didn’t expect to want to live on forever. “If I’m too ill, I don’t have any desire to be lugged around in a wheelbarrow… not at all,” he replied. When asked if he could see himself using assisted suicide, he said, “Yes,” but added, “for now,” reiterating that the decision was “still very difficult.”

When it finally came to making that decision, he made sure he did so with absolute authority over it – like he had done all his life, and in all his works.

None but this titan of the 20th century’s intellectual world had made creative arguments in film with similar convictions. This French New Wave poster boy gave French cinema a personality as he created languages and communicated social concepts with the effectiveness of democratisation.

Also read: How Jean-Luc Godard redefined cinema and influenced Martin Scorsese’s Casino

Godard, a cultural icon of the first order, will always stand for new, intelligent, and revolutionary concepts in film. It is clear that his unconventional strategy did not have a universally good effect. In reality, the majority of his fellow auteurs found great joy in criticising his use of the medium.

Being in awe of his work, or being critical of it are the only two options one has once they are familiar with his filmography. He is a force in cinema to be reckoned with – someone whose ideas and works, cannot be ignored. Even his Nouvelle Vague peer and friend Agnes Varda had once said after a humorous squabble that she can forgive him for anything because of his genius.

“I find it useless to keep offering the public the “auteur.” In Venice, when I got the prize of the Golden Lion I said that I probably deserve only the mane of this lion, and maybe the tail. Everything in the middle should go to all the others who work on a picture: the paws to the director of photography, the face to the editor, the body to the actors. I don’t believe in the solitude of an artist and the auteur with a capital “A.” …in general, there is a tendency today to consider the problems of the director without thinking that behind him there are many other figures equally important in the making of the film,” he said in a 1983 interview with Film Quarterly.

Also read: Jean-luc Godard: Leaving cinema Breathless

He was accurate about the labour that actors and members of the crew put into film productions, as well as the creative outcomes of their work. Few filmmakers, however, did more to pursue the concept of the auteur or to argue for its worth. Authorship is both ubiquitous in Godard’s work—in the way he shattered old cinema’s rote reality to confront an emotional one—and philosophically beset, as a thousand fears and descriptions hedge against even the simplest of stories.

Trying to write anything resembling an obituary for Godard is an endless endeavour. Where do you even begin when it comes to the greatest? How do you grasp an oeuvre that is so distinctive, significant, sad, but beautiful and full of life? Words fail, which is why Godard stopped writing and instead made films.

“Why must one talk?” his character Nana Kleinfrankenheim said in Vivre sa Vie. “Often one shouldn’t talk, but live in silence. The more one talks, the less the words mean.” Godard’s film criticism evolved into filmmaking because the art form was so rich in opportunities and perspectives that he couldn’t obtain them through literature, though there is still a powerful textual element to his films. After all, he did declare that the best way to critique a film is to make your own.

Also read: Jean-Luc Godard: Child of Marx and Coca Cola

His last film, The Image Book, is a spectral essay film that contends, from a variety of perspectives, that Western cinema has worn away reductive narratives about the rest of the world, notably the Middle East, while omitting much of its own history.

The Image Book, primarily a collage, borrows and stitches together bits of other films—some famous, some Godard’s own—to the point where many are barely recognisable, and most come to feel completely new. Without actors or a script, the auteur’s hand extends through time to turn the comfortable in a new pattern, to new lengths.

He was cinema’s true revolutionary – repeatedly redefining, reconstructing, reimagining ideas.

Also read: Adieu Godard: The French filmmaker’s India connection

Therefore, in trying to write anything resembling an obituary for Godard you discover – even though the auteur is dead, his art is now alive, more than ever. And even in death, he exercised the ultimate dominance.

“It was his decision and it was important for him that it be known.”

And if nothing I said convinces you of the stature of the revolutionary figure that Godard was, take it from the journalist who presented the director at the 2001 Cannes Film Festival news conference, “In Godard there is God.”

A comment he would undoubtedly scoff at while lighting his cigar.