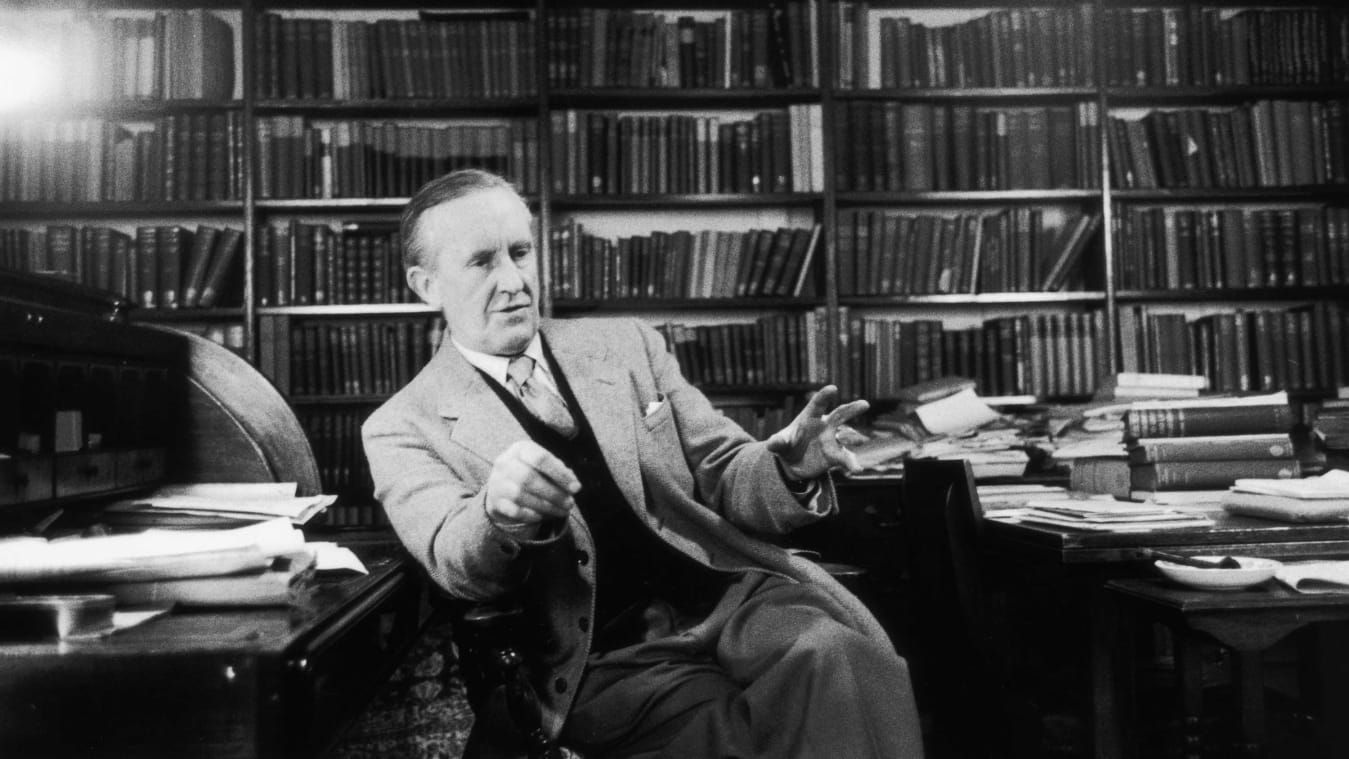

J.R.R. Tolkien, born on January 3, 1892, is largely considered the founder of modern fantasy and remains one of the most popular authors in the world, with book sales in the 250-300 million range.

Those book sales not only touched millions of people throughout the world – but they also inspired two blockbuster film trilogies, earning Tolkien the third highest-earning “dead celebrity” behind Michael Jackson and Elvis Presley, according to Forbes.

Also read: The Weeknd’s new album ‘Dawn FM’ feat. Tyler, the Creator, Lil Wayne, and more to release on Friday

However, Tolkien’s success isn’t solely based on sales and money. His importance has been recognised by people all around the world; in a BBC survey, The Lord of the Rings was chosen the nation’s favourite book, and Amazon consumers voted it the “book of the millenium.”

The Oxford English Dictionary now lists “hobbit,” “eucatastrophe,” and “Tolkienesque” as words that have entered the common language. For writers, entering the Oxford English Dictionary is a rare occurrence, and it implies that Tolkien is a unique kind of author.

Standing in a time where we date virtually and invest in non-fungible art, Tolkien’s work still holds a power of relevance and interest. Aside from the engrossing fantastical narratives coupled with immersive imagination, there are layers of meanings and endless ways of interpretation behind his works, that makes it a stronghold of the popular culture and literary domain at the same time.

Also read: Taliban orders beheading of mannequins in Afghanistan

Presence of antithesis in Tolkien’s work and its indisputable rationale is one of the main reasons of reflectivity that engagement with his creation provides, which in turn builds a ground of relatability, thereby launching the seeds of popularity in our minds, across generations. We can, for our understanding, examine one of his best known works, ‘The Lord of the Rings.’

Good and Evil

A trope as old as time. ‘The Lord of the Rings’ depicts a stark dichotomy of good and evil. Orcs, the most reviled of races, are thought to be a perversion of the Elves, a mystically exalted species.

Mordor, the home of Sauron the Dark, is hostile to Gondor and all free peoples. These antitheses, however many and pronounced, are sometimes thought to be overly polarising, but they have also been claimed to be crucial to the story’s structure.

Also read: Actor Whoopi Goldberg tests COVID positive with ‘mild symptoms’

Theologian Fleming Rutledge claims that Tolkien’s goal is to demonstrate that there is no clear border between good and evil since “‘good’ people can be and are capable of evil under certain circumstances”.

Fate and Free Will

There are two ways we live life. We either surrender to fate or fight for our right to choose. Battles have been fought and empires have fallen in human’s quest to challenge the notion of fate and exercise free will.

The importance given to personal choice and decision in ‘The Lord of the Rings’ contrasts dramatically with the prominent role assigned to fate. The crux of the entire story revolves around Frodo’s voluntary decision to carry the Ring to Mordor.

Frodo’s willing offer of the Ring to Gandalf, Aragorn, and Galadriel, as well as their willing refusal, are as significant, as is Frodo’s final inability to muster the resolve to destroy it.

Pride and Courage

The heroes who destroy the Ring and scour the Shire, according to Tolkien’s biographers Richard J. Cox and Leslie Jones, are “the little guys, literally. The message is that anyone can make a difference.” This is referred to as one of Tolkien’s key themes.

Tolkien compared bravery in the form of devoted allegiance with arrogance in the pursuit of glory. While Sam is loyal to Frodo and would die for him, Boromir is driven by pride in his desire for the Ring and is willing to sacrifice others for his own personal glory.

Death and Immortality

If life was to be compared with any sport, it would be a slow race. We are born, and we know that death is what we are destined for and all our life we spend trying to delay our journey.

Also read: Germany shuts down half of its 6 remaining nuclear plants

“But I should say, if asked, the tale is not really about Power and Dominion: that only sets the wheels going; it is about Death and the desire for deathlessness. Which is hardly more than to say it is a tale written by a Man!” Tolkien himself writes.

His work exemplifies the notion that we are only ever truly free in our deaths. We see that recurring in the tale, including when Aragorn selects the time of his death after more than two hundred years of existence, leaving behind a devastated and now-mortal Arwen, who then travels to the faded ruins of Lothlórien, where she once lived happily, and dies on a flat stone by the Nimrodel River.

There is a certain amount of cynicism that Tolkien provides, carefully balanced out with a message of hope that resonates with the lived reality of all human beings. Tolkien’s work keeps inspiring and teaching generations of people to dream and to dare and be wary. On his 130th birth anniversary, one can well imagine what he would say to us, if he could – ‘Well, I’m back.’

One adventure ends for another to begin.