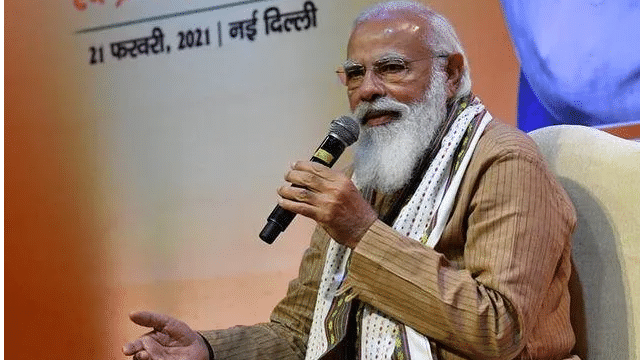

A study by the Lawrence Berkeley National

Laboratory (LNBL), which is a US department of energy’s office of science lab

managed by the University of California, validated the cost-effectiveness of

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s announcement at the UN Climate Change Conference

in Glasgow in October-November that India would install 500 gigawatts (GW) of

renewable energy production capacity by 2030.

Also Read: ‘Wind is ridiculous’: Donald Trump slams Boris Johnson for turning ‘liberal’

The study also projected that if India

achieves the target of installing 500 GW of renewable electricity capacity by

2030, it could reduce electricity costs by 8-10 per cent, provided the

renewable energy and battery storage prices continue to decline.

Carbon emissions will reduce

If this becomes a reality, India will be

able to reduce the carbon emissions intensity of its electricity supply by

43-50 per cent by 2030 over the 2020 level.

France 2030: Macron’s spending spree to oil French growth engines

“We

found that building such high levels of renewable energy would actually be

economical for India, thanks to the cost reductions in clean technologies that

have occurred much faster than anticipated,” said Berkeley Lab scientist and

the study’s lead author Nikit Abhyankar, an Indian-American. “However, the key

to achieving the lowest costs, while maintaining grid reliability, lies in

complementing the renewable energy buildout with flexible resources such as

energy storage and demand response, and utilising the existing thermal power

assets in the country in the most efficient manner,” added Abhyankar.

175 GW by 2022

India has committed itself to install 175

GW of renewable energy capacity by 2022, up from the current 100 GW, and

eventually to 500 GW by 2030.

The study demonstrated that if India hits

the 2030 target, 50 per cent of its electricity supply could come from

carbon-free sources compared to only 25% in 2020.

Also Read: Democratic spirit ingrained in Indians: PM Modi at ‘Summit for Democracy’

However, to achieve the target India would

require quadrupling total renewable energy capacity, the study said. But that

would still be cheaper than building coal- and gas-based plants if the

transition was supplemented by, the researchers found, flexible resources such

as shifting agricultural electricity consumption to solar hours, using batteries

to store four to six hours of daily energy for nighttime use, and utilising

flexibility in existing thermal power plants is cheaper than building new coal-

or gas-based plants.