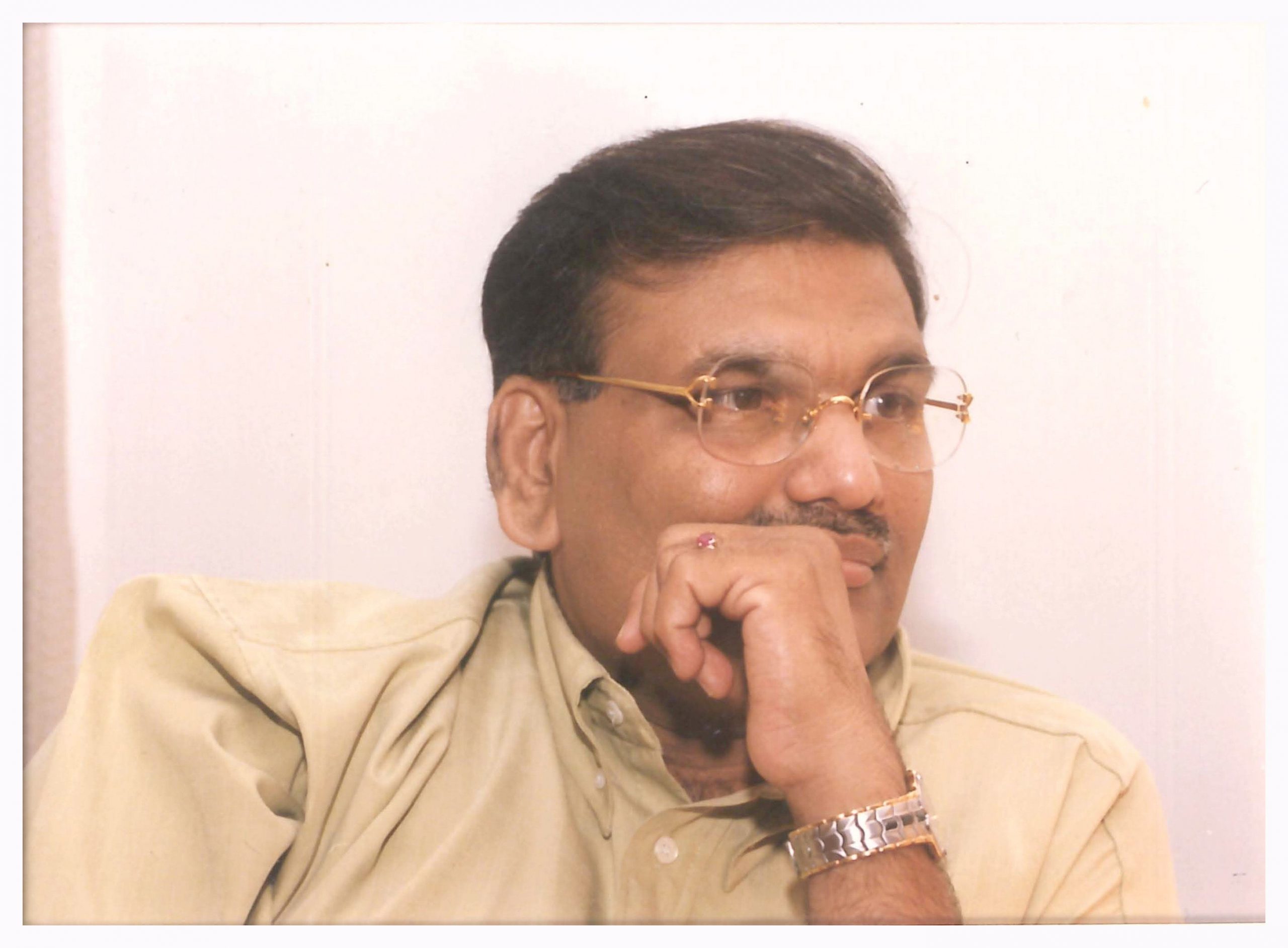

Harshad Mehta also known as the ‘Big Bull’ had become a popular figure on Dalal Street in the early 90s until being charged with a securities scam in 1992, thereby ending his bull run.

As a result of his extravagant lifestyle after rising to the rank of a celebrity stockbroker, Harshad Mehta was frequently referred to as the “Big Bull” of Dalal Street or the “Amitabh Bachchan” of the Indian stock market. The securities scam of 1992 was worth nearly Rs 4,000 crore

Also Read| Harshad Mehta’s wife Jyoti brings Big Bull’s side of story to light

Harshad Mehta effectively managed to influence equities by unlawfully collecting money from many banks using fake bank receipts, as several financial journalists who covered the scandal recall. He set up a vicious circle of fraud that included large names like the State Bank of India (SBI) and the National Housing Bank (NHB).

Also Read| How to survive a market crash

Large-scale modifications were made to the stock market, including a shorter settlement cycle, a minimum balance requirement, and online transactions, among other things.

The fraud, however, consisted of more than simply that. Mehta had also exploited flaws in the country’s banking system.

Also Read| Who is Jyoti Mehta?

Sensex rose from approximately 1,000 points to over 4,500 points between April 1991 and 1992. During this time, Harshad Mehta moved thousands of crores from banks into the stock market.

Also Read| Great Depression to COVID: Top 5 market crashes in American history

When the fraud was uncovered by veteran journalist Sucheta Dalal, it came to light how Harshad Mehta had manipulated stocks using banking loopholes. Shortly after the scam was discovered, the stock market had a massacre that severely harmed Mehta’s assets.

Harshad Mehta’s downfall began when it was revealed that SBI had Rs 500 crore missing from its accounts in the form of a Subsidiary General Ledger (SGL) at the RBI’s public debt office.

This inconsistency prompted the Janakiraman Committee, a Joint Parliamentary Committee created by the central bank, to conduct a more thorough inquiry.

Also Read| US inflation rate at a 40-year high | A timeline: 1930-2022

Harshad Mehta had formed strong relationships in the financial system throughout his climb during the 1980s. Mehta had taken a “shortcut” that the banks used while dealing in government securities, much like many other brokers at the time.

Although RBI norms required banks to engage directly with other banks in security transactions, they decided to depend on brokers since it was faster and easier. Many banks adopted a practice known as ready-forward deals (RFD) to improve the value of their government bond holdings. RFDs were secured, 15-day short-term loans given by one bank to another.

Also Read| How India can fight ransomware attacks

The loans were made in exchange for government securities. As a result, the borrower bank was required to sell securities to the lending bank and then repurchase them at the end of the term at a somewhat higher price.

Harshad Mehta worked as a broker for a number of banks interested in dealing in government securities. He would act as a go-between for banks looking to sell or purchase securities, thereby benefiting himself.

Also Read| Impact of US Feds’ biggest rate hike since 1994 on India

Bank receipts (BRs) were issued at the time by borrower banks to lender banks eager to purchase securities. This meant that no real securities were exchanged, and only BRs were produced.

For example, if one bank wanted to purchase and another wanted to sell securities, Harshad Mehta would contact both banks as a broker. The cycle grew as Mehta increased his dealings with several banks by using forged bank receipts.

It should be emphasised that Harshad Mehta partnered with officials from the Bank of Karad and the Metropolitan Cooperative Bank to obtain fake bank receipts. Mehta utilised these fraudulent bank receipts to steal money from banks, which he subsequently redirected to the stock market.

Also Read| Wall Street enters bear market: What does it mean for investors

Following Sucheta Dalal’s revelation, Mehta’s investors lost trust in him, and a slew of investigating authorities, including the CBI, began looking into him. After spending three months in prison with his brother Ashwin Mehta, he hinted that securities fraud may be connected to a bigger issue.

Following the securities fraud, Harshad Mehta made numerous outrageous statements. One of the assertions was that he obtained government assistance from prominent people. He even claimed to have paid one crore rupees to then-Prime Minister PV Narasimha Rao. The allegations were never proven.

He was later charged and convicted of diverting funds from the public sector Maruti Udyog Limited (MUL) to his own accounts, as well as misappropriating about Rs 2.5 billion. He was detained again by the CBI in 2001 for the latter offence and did not get bail till his death later that year.

Also Read| ‘Scam 1992’ grabs place in IMDb’s ‘Top 10 Indian Web Series of 2020’ list

Many bank employees, brokerage firms, bureaucrats, and even politicians were implicated in the high-profile swindle. Numerous people, including R Sitaraman, who was the focal point of the irregularities at SBI, were found guilty on numerous charges of fraud.

Following the scam, the majority of Harshad Mehta’s and his family’s assets were seized by various agencies, and he was hit with massive income tax fines.

More than 600 civil lawsuits were filed against Harshad Mehta and his family members in addition to 76 criminal charges. All criminal actions against Mehta were dropped shortly after his death in Tihar prison, but a large number of civil suits to recover debts from his family remain intact.