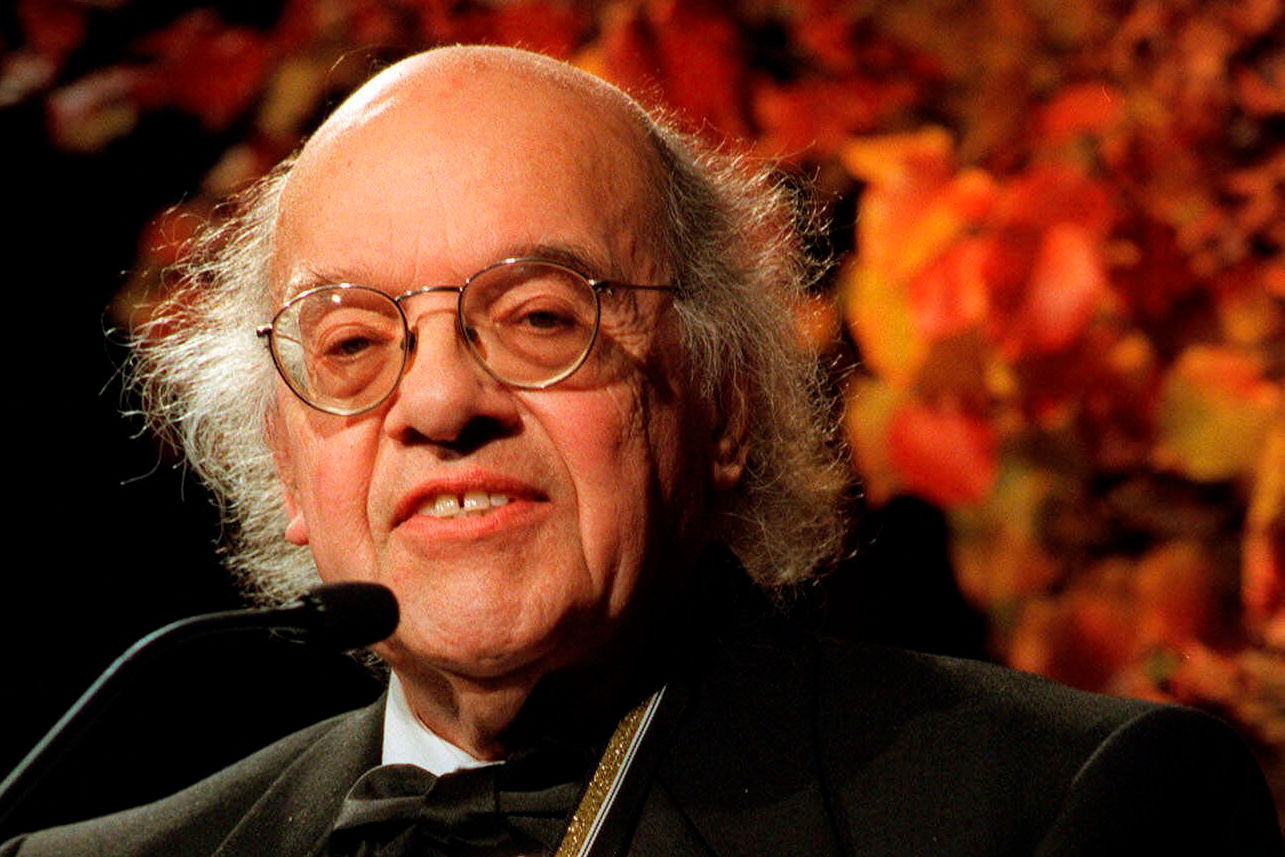

Gerald Stern, one of the most adored and revered American poets, has died. He was known for his passionate sadness and earthy humour and his poems about his childhood, Judaism, mortality, and the wonders of the contemplative life. He was 97.

According to his lifelong partner Anne Marie Macari, Stern, who served as the first poet laureate of New Jersey, died on Thursday at the Calvary Hospice in New York City. The cause of death was not disclosed in a statement from Macari which publisher WW Norton released on Saturday.

Also read: Jerry Lee Lewis: Controversy’s favourite child

The balding, round-eyed Stern, who won the National Book Award in 1998 for the anthology This Time, was frequently likened to Walt Whitman and Allen Ginsberg because of his poetic, sensual style, and his talent for uniting the material world with the larger cosmos.

Stern was shaped by the rough, urban surroundings of his native Pittsburgh, but he also identified strongly with nature and animals, marveling at the “power” of a maple tree, likening himself to a hummingbird or a squirrel, or finding the “secret of life” in a dead animal on the road.

Also read: Jerry Lee Lewis dead: Know all about his net worth, wives, children

A lifelong agnostic who also fiercely believed in “the idea of the Jew,” the poet wrote more than a dozen books and described himself as “part comedic, part idealistic, colored in irony, smeared with mockery and sarcasm.” In poems and essays, he wrote with special intensity about the past — his immigrant parents, long-lost friends and lovers, and the striking divisions between rich and poor and Jews and non-Jews in Pittsburgh. He regarded The One Thing in Life, from the 1977 collection Lucky Life, as the poem that best defined him.

___

There is a sweetness buried in my mind

there is water with a small cave behind it

there’s a mouth speaking Greek

It is what I keep to myself; what I return to;

the one thing that no one else wanted

___

He wasn’t given any significant honours until he was past 50, although he received many citations in the latter half of his life. In addition to his National Book Award, he also received lifetime achievement distinctions like the Wallace Stevens Award and the Ruth Lilly Prize for his work on Leaving Another Kingdom, which was a 1991 Pulitzer Prize nominee.

In 2013, the Library of Congress gave him the Rebekah Johnson Bobbitt National Prize for Early Collected Poems and praised him as “one of America’s great poet-proclaimers in the Whitmanic tradition: With moments of humor and whimsy, and an enduring generosity, his work celebrates the mythologizing power of the art.”

Also read: Leslie Jordan, Emmy-winning actor, and comedian, dies at 67

Meanwhile, he was named New Jersey’s first poet laureate, in 2000, and inadvertently helped bring about the position’s speedy demise. After serving his two-year term, he recommended Amiri Baraka as his successor. Baraka would set off a fierce outcry with his 2002 poem Somebody Blew Up America, which alleged that Israel had advance knowledge of the Sept. 11 attacks the year before. Baraka refused to step down, so the state decided to no longer have a laureate.

Stern, born in 1925, remembered no major literary influences as a child, but did speak of the lasting trauma of the death of his older sister, Sylvia, when he was 8. He would describe himself as “a thug who hung out in pool halls and got into fights.” But, he told The New York Times in 1999, he was a well-read thug who excelled in college. Stern studied political science at the University of Pittsburgh and received a master’s in comparative literature from Columbia University. Ezra Pound and W.B Yeats were among the first poets he read closely.

Also read: Robbie Coltrane: Harry Potter star died of six causes including multiple organ failure

Stern lived in Europe and New York during the 1950s and eventually settled in a 19th-century home near the Delaware River in Lambertville. His creative development came slowly. Only during free moments in the Army, in which he served for a brief time after World War II, did he conceive the “sweet idea” of writing for a living. He spent much of his 30s working on a poem about the American presidency, The Pineys, but despaired that it was “indulgent” and “tedious.” As he approached age 40, he worried that he had become “an eternally old student” and an “eternally young instructor.” Through his midlife crisis, he finally found his voice as a poet, discovering that he had been “taking an easier way” than he should have.

Also read: Who was Tristen Nash, American wrestler Kevin Nash’s only son, dead at 26?

“It also had to do with a realization that my protracted youth was over, that I wouldn’t live forever, that death was not just a literary event but very real and very personal,” he wrote in the essay Some Secrets, published in 1983. “I was able to let go and finally become myself and lose my shame and pride.”

His marriage with Patricia Miller was annulled. David Stern and Rachael Stern Stern were their two children.

Stern was a longstanding political activist whose causes included racial integration at a swimming pool in Indiana, Pennsylvania, and planning an anti-apartheid reading at the University of Iowa. Stern tended to steer clear of topical poems, though.

He was a teacher at several different institutions, but he was very pessimistic about academic life and writing programmes. He made a point of scaling the wall on his route to class at Temple University because he was furious at the institution’s choice to build a 6-foot brick wall dividing the university from the surrounding Black neighbourhoods of Philadelphia in the 1950s.

Also read: George Floyd’s family plans to sue Kanye West for $250 million for false claims about his death

“The institution subtly and insidiously works on you in such a way that though you seem to have freedom you become a servant,” he told the online publication The Rumpus in 2010. “Your main issue is to get promoted to the next thing. Or get invited to a picnic. Or get tenure. Or get laid.”

Besides Macari and his children, Stern is survived by grandchildren Dylan and Alana Stern and Rebecca and Julia Martin.