Sinamangue Tamu is still just a teenager, but now has the responsibility of parenting her three little brothers after they fled a brutal Islamist insurgency in which their northern Mozambican town was seized.

They were separated from their father while escaping the port town of Mocimboa da Praia — his whereabouts are still unknown.

“I don’t know if he’s alive or dead,” Tamu said, avoiding eye contact. Their mother had died of an illness.

Tamu is sitting on a mat in a camp for internally displaced people on the outskirts of Pemba, the capital of Cabo Delgado province, where the insurgency was launched three years ago.

Her youngest brother is under two years old and always clings to her, whether sitting in her lap or strapped to her back with a capulana — a colourful Mozambique sarong.

Pausing between sentences, Sinamanga told AFP she was worried about her toddler brother.

“He is refusing to eat the food we have here. At the hospital they say he has anaemia. He doesn’t eat,” she said.

The diet of chickpeas and corn flour is monotonous for the around 600 families at this dilapidated former agriculture training college in Metuge, 45 kilometres (28 miles) from Pemba.

They are just a few of the half million people forced from their homes by the vicious jihadist campaign in northern Mozambique, which is estimated to have killed more than 2,400 people.

For women and adolescent girls at the camp, life is a daily grind of chores — washing, cooking, caring for children.

Men meanwhile gather idly under trees worrying about their future, having left everything behind.

The Islamist insurgency has intensified in recent months, with torched villages and atrocities including beheadings increasing.

The painful memories of such atrocities can be seen etched on the faces of many at the camp.

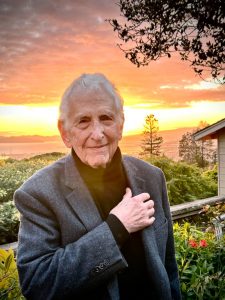

Isa Ali, 53, fled when the Islamist militants set fire to his village near Mocimboa da Praia. He hid in the bush until they left, returning to discover that he had lost everything.

He walked until he ended up at the camp. He has no news of his wife and 10 children.

Now he says sleeping on the concrete floor is making him sick.

“We are not animals, animals sleep in the sand,” he said.

“Here we don’t eat properly; they give us a bag of 50 kilos (110 pounds) of peas for 30 days… without oil. It’s just water and salt and peas.”

He is not the only one struggling.

“Mr journalist, in this centre we are hungry,” said a man who only gave a first name, Ramadan.

He warned that it would not be a surprise if people start dying from hunger “because the food is not enough — and the government knows that.”

Bartolomeu Muibo, the former administrator of Quissanga district, is among those displaced and living in the camp after fleeing his home in April.

He acknowledged the government is struggling to meet everyone’s needs.

“We have just the basics to survive. But it’s not enough. The diet is an important component to ensure health and food security, especially for children,” he said.

Charities offering humanitarian aid say they are working hard to ensure supplies reach those in need, but insecurity hampers access to some areas.

“The humanitarian situation here in Cabo Delgado as well as the neighbouring provinces of Niassa and Nampula is really challenging at the moment,” Sascha Nlabu, the International Organization for Migration’s operations chief in Mozambique, told AFP.

Manuel Nota, the Pemba director for Catholic relief services charity Caritas, said the displaced were living in “unacceptable conditions”.

“For example, a tent designed for 10 people, houses 30 to 40 people,” he said, adding that blankets and kitchen supplies were also needed.

“We couldn’t cover it.”