The term Afrofuturism was coined by Mark Drey, a journalism professor at New York University in a 1993 essay called Black to the Future. It was made famous by Marvel Cinematic Universe’s Black Panther film series by taking it from the academic fringe to the mainstream of global African-American culture.

Even before Frey defined the genre, a number of works in music, art, film, literature and comics with these broad themes had sprung up, and even more have done since. With 2022 film Black Panther: Wakanda Forever already in the theatres, it’s worth revisiting the film’s role in making Afrofuturism mainstream.

Also read: Ryan Coogler, Letitia Wright, Angela Bassett open up about dealing with Chadwick Boseman’s death

What is Afrofuturism?

Afrofuturism falls under the genre of speculative science fiction where the main tenet is to imagine an alternative future, based on an alternative past, that helps to negotiate real-life struggles of the present. The bodies of black people are controlled, histories are erased and alien technology is imposed on their everyday lives. Afrofuturism provides an outlet in art and culture to negotiate this lived experience.

“African-Americans, in a very real sense, are the descendants of alien abductees,” writes Mark Dery in Black to the Future. He says that the African-American experience in a white man’s world is a “sci-fi nightmare” where forces not under the control of black people frustrate them frequently. As a result, alien abduction, time travel, and futuristic societies are often common themes in Afrofuturism.

By imagining an alternative world, Black people can construct a “space of agency, joy, and true freedom”, according to John Jennings, a culture and media studies professor at the University of California Riverside.

“The future for black people in America was supposed to be connected to only three spaces: one, the hold of a slave ship; two, the plantation; and three, the grave,” Jennings tells Vox’s Hope Reese in an interview. “The construction of a space of agency, joy, and true freedom has always been the central focus of black speculative culture. As exciting as Black Panther himself is, his light can never be brighter than the idea of Wakanda,” she adds.

Also read: Black Panther Wakanda Forever: Tony Stark’s Ironheart connection explained

Afrofuturism, Black Panther and the global African

One of the key features of Afrofuturist works is the positive, hopeful outlook it generates by constructing an imaginary space. of Black freedom. Wakanda can evade the forces of history and exist as a vision of a world where colonialism never happened. Through this imagination, it can empower the Black identity.

When the first film starring Chadwick Boseman was released on February 16, 2018, it opened up a celebration of African-American culture that was never seen before in Hollywood. A full black cast walked red carpets with traditional African American dresses. Some even had tribal art and designs on bodies and faces. No wonder, even at the theatre lines, there were more people than ever wearing Black dresses like fur coats, dashikis, crowns, lion sashes, and outfits inspired by precolonial African kingdoms.

Added to that is the extent to which the film has made Black culture global by increasing its acceptance in other cultural communities.

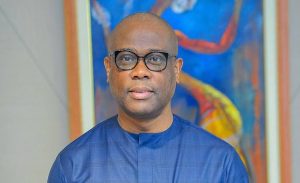

Ayodeji Aiyesimoju, a lecturer in media studies at Joseph Ayo Babalola University in Nigeria, told Reuters that Black Panther opened up questions about Africa and made people more interested in the continent.

“It opened conversations for questions. People were genuinely interested in knowing about the continent,” he said.

Even Lupita Nyong’o, the actor who plays Nakia in Back Panther, agreed with Aiyesimoju. “Embracing the diversity that is African culture has resulted in other people embracing their indigenous cultures as well,” she told Reuters.

Also read: Serena Williams on Black Panther Wakanda Forever: Best Marvel movie ever

However, for black people, Black Panther’s importance lies in how it expanded what Blackness means. The film helped to create a “fictive kinship” which is not related to the DNA but rather depends on shared experience, according to scholars Myron T. Stron and Sean Chaplin. It helped them find common causes and strike a sense of unity that is as real as possible in spite of being rooted in fiction.

Talking about the Atlantic slave trade, poet Amiri Baraka once wrote “At the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean there’s a railroad made of human bones.” Irrespective of the internal differences and diversity that characterise the Black experience, there is consensus on the fact that it would have been vastly different if colonialism did not exist.

While that consensus does not stand the test of history, hope in the face of real oppression becomes meaningful, even if it’s after all imaginary.