For

months now, public health experts have chafed about vaccine nationalism- when a

country manages to secure doses of vaccines for its own citizens and prioritises

its own domestic markets before they are made available in other countries.

For

example, the United States, the United Kingdom, Japan, and the European Union

have spent tens of billions of dollars on deals with vaccine front runners such

as Pfizer Inc, Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca Plc even before their

effectiveness is proven.

The

concerns arise when these advance agreements are probably to make the vaccine

unattainable to large parts of the world that do not have the money to receive

and vaccinate their native population.

The major

drawback of vaccine nationalism is that it puts countries with fewer resources

and bargaining power at a disadvantage. Thus, if countries with a large number

of cases lag in obtaining the vaccine, the disease will continue to disrupt

global supply chains and, as a result, economies around the world.

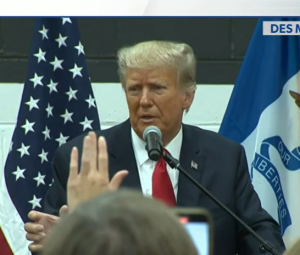

Like

Trump, Johnson may face a sizable contingent of compatriots who refuse to get a

vaccine because they do not trust the government or public health experts. The

British leader said he would “strongly urge” people to get vaccinated, but said

it is “no part of our culture or our ambition in this country to make vaccines

mandatory.”

Even

though vaccine nationalism runs against global public health principles, there

are no provisions in international laws that prevent pre-purchase agreements.

Aforementioned

incident

There

have been precedents: In 2009, following an outbreak of H1N1 influenza, or

swine flu, rich countries had hoarded vaccines in a way similar to the

pre-booking happening now. As a result, many countries in Africa had no access

to these vaccines for months. The US and some European countries finally agreed

to release 10% of their stocks for other countries, but only after it had

become evident that they did not need the vaccines for themselves any longer.

Similarly,

anti-retroviral drugs for the treatment of HIV patients were unavailable in

Africa, the worst affected region, for several years after being developed in

the 1990s.

Scientists

and experts have been maintaining that such a strategy might not work out very

well even for the countries that can stock up on the vaccines. If some parts of

the world continue to reel under the epidemic because of a lack of access to

the vaccine, it would keep the virus in circulation for much longer than it

would otherwise have been. That would mean that other countries too would

remain at risk, at least economically, because of continued disruptions in

global supply chains due to movement, work, and trade restrictions in large

parts of the world.