Two onetime outsiders hailing from opposite extremes of the political spectrum received the most votes Sunday in Chile’s presidential election but failed to garner enough support for an outright win, setting up a polarizing runoff in the region’s most advanced economy.

José Antonio Kast, a lawmaker who has a history of defending Chile’s military dictatorship, finished first with 28% of the vote compared to 26% for former student protest leader Gabriel Boric.

Also Read | Venezuela votes in regional election under international eye

Kast, in a victory speech, doubled down on his far right rhetoric, framing the Dec. 19 runoff as a choice between “communism and liberty.” He blasted Boric as a puppet of Chile’s Communist Party — a member of the broad coalition supporting his candidacy — who would pardon “terrorists,” be soft on crime and promote instability in a country that has recently been wracked by protests laying bare deep social divisions.

“We don’t want to go down the path of Venezuela and Cuba,” Kast, speaking from a lectern draped with a Chilean flag, told supporters in the capital. “We want a developed country, which is what we were aiming to become until we were stopped brutally by violence and the pandemic.”

Also Read | Voters cast ballots in bellwether Malaysian state election

In sharp contrast, Boric refrained from attacking Kast by name, accepting the results with humility and urging his supporters to listen to and convince doubters who voted for other candidates.

“Our crusade is for hope to defeat fear,” said Boric, speaking through a mask to supporters in his home town at the southern tip of the vast Patagonia region. “Our duty today is to convince others that we offer the best path to a more fair country.”

A candidate who ran virtually from the U.S. without stepping foot in Chile led the pack of five other candidates trailing far behind. In Chile’s electoral system, if no candidate secures a 50% majority, the two top finishers compete in a runoff.

Also Read | Republicans lead House in Virginia after result certification, 2 recounts possible

The vote followed a bruising campaign that laid bare deep social tensions in the country. Also up for grabs is Chile’s entire 155-seat lower house of Congress and about half the Senate.

Boric, 35, would become Chile’s youngest modern president. He was among several student activists elected to Congress in 2014 after leading protests for higher quality education. If elected he says he will raise taxes on the “super rich” to expand social services and boost protections of the environment.

He’s also vowed to eliminate the country’s private pension system — one of the hallmarks of the free market reforms imposed in the 1980s by Gen. Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship.

Kast, 55, from the newly formed Republican Party, emerged from the far right fringe after having won less than 8% of the vote in 2017 as an independent. But he’s been steadily rising in the polls this time with a divisive discourse emphasizing conservative family values as well as attacking migrants — many from Haiti and Venezuela — he blames for crime.

A fervent Roman Catholic and father of nine, Kast has also taken aim at the outgoing President Sebastian Pinera for allegedly betraying the economic legacy of Pinochet, which his brother helped implement as the dictator’s central bank president.

Sebastian Sichel, a center right candidate who took around 12% of the vote, was the first among the losing candidates to position themselves in what’s likely to be a heated runoff, telling supporters that under no circumstances would he vote for “the candidate from the left,” a reference to Boric.

Meanwhile, Yasna Provoste, who finished with a similar amount, told her supporters on the center left that she could never be neutral in the face of a “fascist spirit that Kast represents.”

Whoever wins will take over a country in the grips of major change but uncertain of its future course after decades of centrist reforms that largely left untouched Pinochet’s economic model.

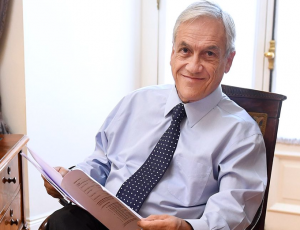

Pinera’s decision to hike subway fares in 2019 sparked months of massive protests that quickly spiraled into a nationwide clamor for more accessible public services and exposed the crumbling foundations of Chile’s “economic miracle.”

Gravely weakened by the unrest, Pinera begrudgingly agreed to a plebiscite on rewriting the Pinochet-era constitution. In May, the assembly charged with drafting the new magna carta was elected and is expected to conclude its work sometime next year.

Meanwhile, in a fresh sign of the tensions Pinera will leave behind, the billionaire president was impeached in the lower house before dodging removal by the Senate over an offshore business deal in which his family a decade ago sold its stake in a mining project while he was serving the first of two non-consecutive terms.