For the first time, an American research team claims to have cured HIV in a woman. These researchers utilised a cutting-edge stem cell transplant procedure that they anticipate would expand the pool of people who could undergo such treatment to several dozen each year, building on previous successes as well as failures in the HIV-cure research area.

Also read: New ‘highly virulent’ HIV strain found; here is why you need not worry

Their patient joined an exclusive group of three men who have been cured, or are extremely likely to be cured, of HIV. Researchers also know of two women whose immune systems have seemingly defeated the virus, which is pretty remarkable.

The accumulation of repeated apparent victories in curing HIV “continues to provide hope,” according to Carl Dieffenbach, director of the Division of AIDS at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, one of multiple divisions of the National Institutes of Health that funds the research network behind the new case study.

“It’s important that there continues to be success along this line,” he remarked.

Also read: HIV patient with COVID developed 21 mutations of coronavirus: Study

Investigators treated Timothy Ray Brown, an American, for acute myeloid leukaemia, or AML, in the first case of what was eventually termed a successful HIV treatment. He had a stem cell transplant from a donor with a rare genetic mutation that confers inherent HIV resistance to immune cells that target the virus. Brown’s technique, which was originally made public in 2008, appears to have cured HIV in two other persons. However, it has failed in a number of other instances.

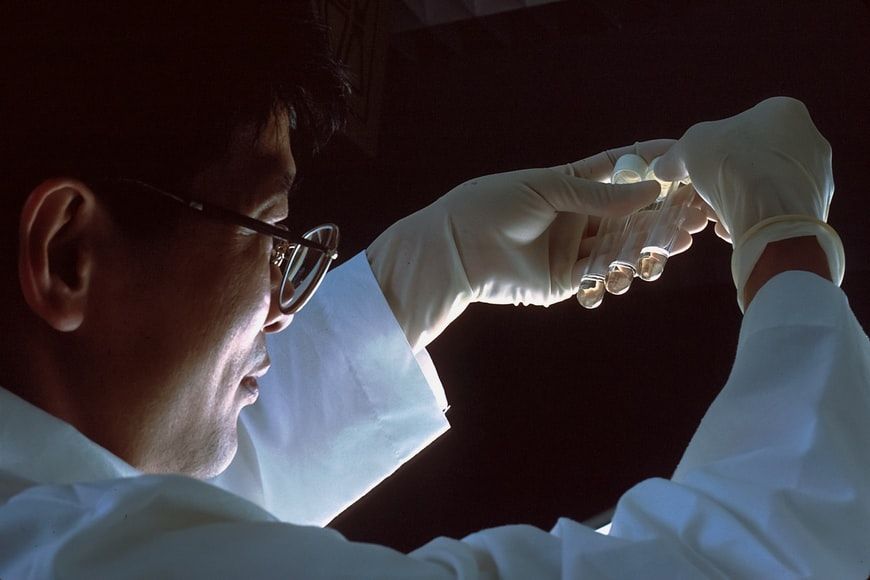

This treatment aims to replace an individual’s immune system with that of another person, treating cancer and curing HIV at the same time. First, doctors must use chemotherapy and, in certain cases, irradiation to eliminate the original immune system. The expectation is that by doing so, as many immune cells as possible that are still harbouring HIV despite adequate antiretroviral treatment will be destroyed. New viral copies that might develop from any residual infected cells will therefore be unable to infect any other immune cells, assuming the transplanted HIV-resistant stem cells engraft adequately.

Also read: Who was Luc Montagnier, late Nobel laureate credited for discovering HIV?

Experts say it’s unethical to try to cure HIV with a stem cell transplant — a toxic, often lethal process — in someone who doesn’t already have a possibly fatal cancer or other illness that qualifies them for such risky treatment.

Dr. Deborah Persaud, a paediatric infectious disease specialist at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and chair of the NIH-funded scientific committee behind the new case study (the International Maternal Pediatric Adolescent AIDS Clinical Trials Network), said that “while we’re very excited” about the new case of possible HIV cure, stem cell treatment is “still not a feasible strategy for all but a handful of the millions of people living with HIV.”