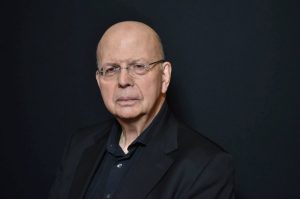

Jean-luc Godard, the

French filmmaker, has died aged 91, leaving his legions of fans in dire need of

a world cinema figure who can be called a true guiding light in these times of never-ending

sequels and spinoffs. Godard was a figure who took his politics as seriously as

his films, and no wonder, when protesting outside the Cannes Film Festival in

1968, the Breathless filmmaker was able to proclaim loudly to the who’s-who of the

film world, “We’re talking solidarity with students and workers, and you’re

talking dolly shots and close-ups. You’re idiots!”

Godard started

his career as a film critic for the Cahiers du Cinema magazine founded by Andre

Bazin. Along with his friend and fellow French New Wave director, Francois

Truffaut, Godard lambasted the French films of the 40s and 50s for being too

polished and too devoid of a connection to the lives of the ordinary French

people. They turned their attention to American and British cinema during this

time. The aesthetics of film noir movies in works like Billy Wilder’s

Double Indemnity and John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon were what they were

aiming towards. Even Alfred Hitchcock, who was known as nothing more than a successful

thriller director in the English-speaking world, was first acknowledged as a

true master of the cinematic art form by the Cahiers’ critics.

Also Read| Jean-Luc Godard: 5 lesser-known facts about the French filmmaker

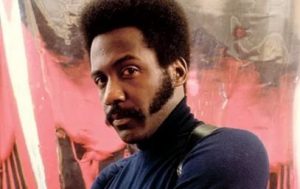

Godard began his filmmaking

career in 1960 with a script written by Truffaut, who had by then already stirred

the world with his debut feature, 400 Blows. Godard roped in an unknown actor, Jean-Paul Belmondo, as the lead, and chose to shoot his movie outside of

the confines of the film studios. Edit jerks, jump cuts, and poetry between the

lines of an otherwise ‘gangster’ story would be the hallmarks of Breathless and

would go on to define his nearly six-decade-long career.

Also Read| Emmanuel Macron on Jean-Luc Godard’s death: France lost a ‘national treasure’

The movies of this

maverick genius were more like a statement against established norms. He took an

otherwise average story and then infused it with his own philosophies and references.

Let’s take the example of his second feature, La Petit Soldat. The film revolves

around Bruno Forestier, a man who is hiding in Geneva in order to avoid getting

enlisted in the French Army. He is, however, captured by La Main Rouge, a

terrorist organization operated by the French intelligence service to quash the

pro-independence movement for Algeria. When tasked with murdering an FLN (National

Liberation Front of Algeria) activist, he refuses to go ahead with the task. Forestier

is soon kidnapped by FLN workers who torture him for information about

La Main Rouge. And between those torture scenes, Forestier and the

revolutionaries extensively discuss their Maoist and Leninist ideologies.

Also Read| Jean-Luc Godard: Child of Marx and Coca Cola

Another famous filmmaking

technique Godard popularized, which has now been adopted in movies like

Deadpool to shows like Fleabag, is the idea of breaking the fourth wall, where the

characters and the audience are both aware that what they are watching is a

manifested reality. Forestier, while giving a voice-over narration in La

Petit Soldat, suddenly says after the torture scene, “Torture is monotonous and

sad. It’s hard to talk about it. I’ll do so as best I can”. In another of his

famous works, Contempt, the lead character is a writer who has been assigned

the task of rewriting a film script of a Fritz Lang production. In the very

first few scenes, we see him talking to the director and producer on a film set.

And guess who is assisting Lang in the movie? Godard himself.

Also Read| Jean-Luc Godard best quotes on cinema

Giving established genres

a new spin is something the French genius was a master at. He delved into science

fiction with the 1965 production, Alphaville, and instead of going for big sets

and futuristic props, he depicted Paris of the 60s as a technocratic city of

the future. Lightings and the new modernist architecture that was coming up in Paris at

that time, provided the right ambience for the film. Despite being set in the

future, Godard makes it a point to discuss 20th century events in

the film extensively, referring to the period’s icons like Jean Cocteau, Henri

Bergson, and Louis-Ferdinand Celine. There are a number of similarities between

Cocteau’s 1950 film, Orpheus, and Godard’s Alphaville.

At the height of his

fame in 1968, fresh off the success of Week-end, Godard and fellow Marxist

intellectual Jean-Pierre Gorin, Godard began the Dziga Vertov movement, making

a set of documentaries and features where they did show credits on-screen. Experimenting

and moving the art form ahead from where he found it when he entered the scene

would be the late filmmaker’s watchword for life. He carried on the spirit even

in later, more abstract works like Goodbye to Language and The Image Book.

Also Read| Jean-Luc Godard, godfather of French New Wave cinema, dies at 91

Godard’s life is one of

style and substance; he became a poster boy of sorts for the ones who wanted to

bend the rules. He was trashed by Bergman, who remarked about him, “I’ve never

gotten anything out of his movies. They have felt constructed, faux

intellectual and completely dead. Cinematographically uninteresting and

infinitely boring”, but was adored by people who came after. Quentin Tarantino said

about the La Chinoise director, “To me, Godard did to movies what Bob Dylan did

to music: they both revolutionised their forms.” And that is exactly what Godard

will be remembered as. Someone who strived to break the norms till the very end

and expand the limits of the field that they have decided to dedicate their lives

to.